Omair Anas

While visiting Turkey’s spiritual sites, one would be surprised to encounter the omnipresence of a book called “Mektubat-ı Rabbani,” the collection of letters of the famous 16th-century Indian Sufi, Ahmad al-Faruq al-Sirhindi, also known as Imam Rabbani (1564–1624). Why did an Indian Sufi become so popular in Turkey?

The records of heavy traffic of Sufi travelers between India and Turkey between the 14th to 19th centuries explain why and how Istanbul and other Ottoman cities became centers for Indian Sufis. According to Christopher D. Bahl, assistant professor at Durham University, among the earlier Islamic scholarly texts brought to Istanbul, there are the works of al-Muḥammad al-Damamini (d. 1424) and Shihab al-Din al-Dawlatabadi (d. 1445). However, the Sufi networks had started spreading from the time of the Delhi Sultanate, an Islamic empire based in modern India’s Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent for 320 years (1206–1526).

A journey of interaction

Throughout history, the cultural exchanges between Muslims and Hindus were observed. While Hindu scriptures became a point of scholarly debate among Muslim Sufis, several important scriptures and popular works were translated from Sanskrit to Persian and Arabic. Based on Islamic sources and principles, Indian Sufis however established their own schools, which also became popular in modern Syria’s Aleppo, modern Iraq’s Baghdad, modern Turkey’s Istanbul and Edirne, even modern Bulgaria’s Sofia and modern Kosovo’s Prizren. The very Sufi centers are known as “tekke” in Turkish or “takiya” in Urdu.

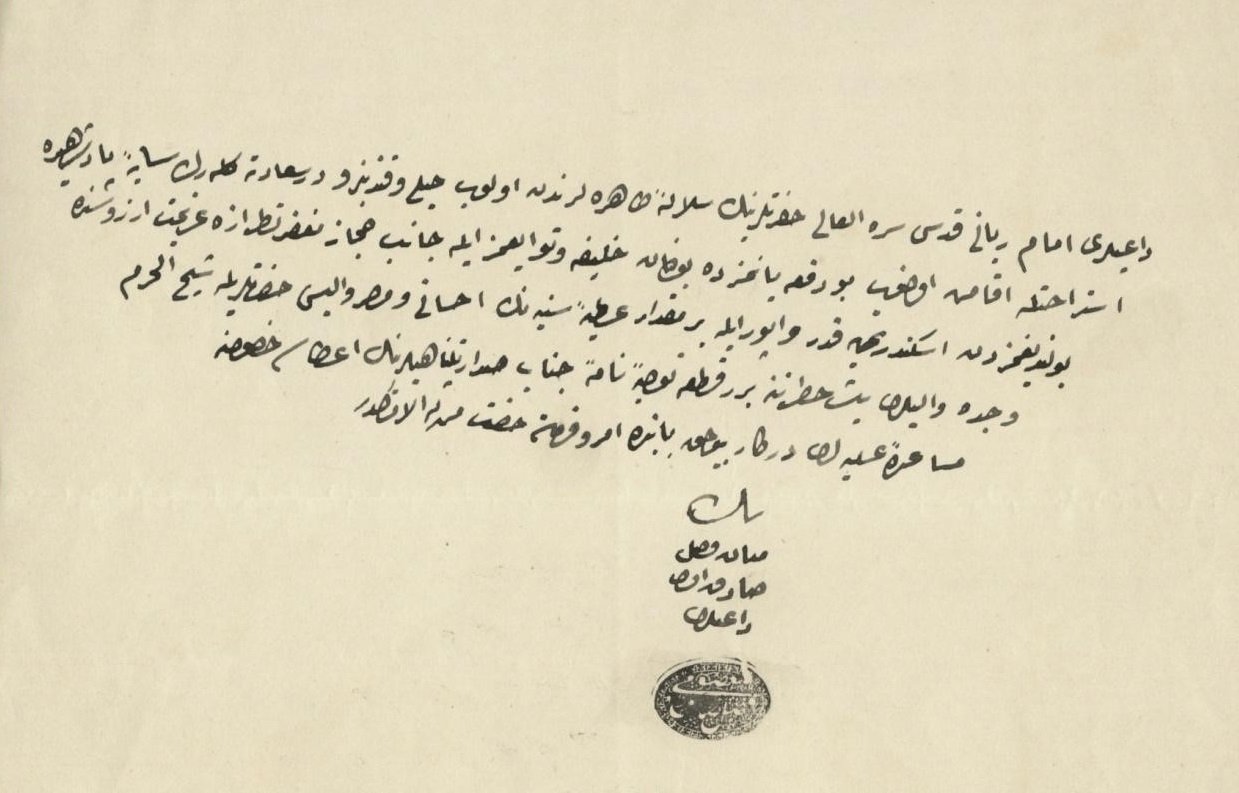

What archives say

There are nearly 150-200 Ottoman-era archives that mention the presence of Indian Sufis in Ottoman cities. According to the earliest reference of the Indian tekkes, in 1581, Indian Sufis arrived in the Bulgarian cities of Sofia and Pazardzhik (Pazarcık) and were generously supported by the Ottoman sultans. For example, the Indian Sufi circles were active in the former Ottoman capital of Bursa, located in today’s western Turkey, and Üsküdar, a historical district of Istanbul. They remained active for more than two centuries and helped the spread of the Sufi order across the region.

For example, one of the most well-known tekkes in Istanbul is the Horhor tekke in Üsküdar, which has recently been renovated. Some Mughal and other Indian diplomatic missions acknowledged the Horhor tekke. Imam Muhammed Serdar was a member of the diplomatic delegation of Tipu Sultan, ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India in the 18th century, and had stayed at this tekke where he was buried after he died. Buta Singh Uppal, later known as Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi, a great freedom fighter for India’s independence, also used to stay at the Horhor tekke to consult with Turkish politicians and Abdur Rahman Peshawari, or Abdurrahman Bey, who would later be known as the Indian freedom fighter in Turkey. Abdurrahman Bey had convinced Sindhi about the reforms undertaken by Turkey’s founding leader Mustafa Kemal Atatürk after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

Imam Rabbani’s popularity

The background of Imam Rabbani’s popularity is no less interesting. Here are some anecdotes from his lifetime according to Ottoman archives.

The Baghdad-based famous Sufi Khalid-i Shahrazuri met the Indian traveler and spiritual seeker Mirza Rahimullah Azimabadi, who told him about Imam Rabbani and his disciple Abdullah Dihlevi. Shahrazuri took no time in visiting Delhi in 1809 and attended the circles of Imam Rabbani’s disciples, especially of Dihlevi. He spent more than a year learning the teachings of Imam Rabbani. Shahrazuri returned to Baghdad in 1813. As per the Ottoman archives, Dihlevi also sent his disciples to Anatolia to establish tekkes.

In 1829, one of the grandsons of Imam Rabbani, Halil Efendi, arrived in Turkey’s Ordu province in the Black Sea region, where the Ottoman authorities warmly welcomed him and facilitated his smooth travel and stay.

Sheikh Masumi, a family member of Imam Rabbani, sent a request to travel to Mecca and Medina via Alexandria, asking for a reference letter from the Ottoman authorities. Masumi later died along his journey in 1862.

The extended family members and disciples of Imam Rabbani continued to receive special attention and hospitality from the Ottoman officials and were lodged in Mecca, Istanbul and other places on their visits. According to one document, a member of Shahrazuri’s tekke, Abdurrahman Efendi, was commissioned to translate Imam Rabbani’s letters and works. He died in 1853 but the translation honorarium continued. However, there is no evidence that another famous translation by the 18th-century Ottoman memoir scholar and Sufi Müstakimzade Süleyman Sadeddin, which was completed in 1780, was part of this translation project.

Researchers and academicians pay great attention while tracing the memories of Indian Sufis’ presence in Turkey. A recent book by Turkish academic Ali Emre Işlek, “Osmanlı Coğrafyasındaki Hintli Mutasavvıflar ve Tekkeleri” (“Indian Sufis and Tekkes in Ottoman Lands”) covers most archival references. Historian Rishad Choudhury’s “The Hajj and the Hindi: The ascent of the Indian Sufi lodge in the Ottoman empire” and the previous works of others including academic Mehmet Baha Tanman provide detailed information on the exchange of Sufi traditions between India and Turkey.

Many of these tekkes might have lost much public attention but they remain part of spiritual memories whenever Sufis travel to Turkey. As Turkey is trying to reach out via its Asia Anew initiative, the revival and reintroduction of Indian Sufi memorials in Turkey would greatly help the initiative and reconnect India-Turkey relations beyond political exchanges.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PhD in Middle East Studies from the School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

Courtesy: DAILY SABAH